Werfel and Zionism

In mid- January 1925, Werfel and Alma embarked on their first long trip into the Middle East. The initiative for this trip had been entirely Alma’s, as Werfel was loath to leave familiar surroundings. But as soon as preparations had been made he enjoyed the project immensely and became an enthusiastic traveler. They embarked on the steamship Vienna in Trieste, and the first leg of their journey took them to the Egyptian port of Alexandria.

|

|

| |

|

Franz Werfel In Jerusalem (1920s) |

|

| |

|

| |

|

On board the Vienna were also a great number of Jewish emigrants en route to Palestine to settle their old - and new - homeland. Thus, that homeland was under a British mandate, as was Egypt, but the Balfour Declaration of 1917 allowed Jews to start their own settlements in Palestine and thus move considerably closer to Theodor Herzl’s dream of the return to Israel. Still aboard the Vienna, Werfel noted in his “Egyptian Diary” that the Zionists were regrettably repeating the anachronistic mistake of nationalism: the Jews believed, Werfel wrote, that they were compelled to prove that they, too, could “do the same thing they have so despised and mocked in other nations.”

|

|

| |

|

| |

Bedouins |

| |

|

Werfel and Alma spent three weeks in Egypt. They visited the royal tombs at Thebes, went to Heliopolis, Memphis, Karnak, and Luxor, on to Cairo and the pyramids at Giza. They saw a performance of Verdi’s Aida on the stage of its world premiere, the Italian Opera House in Cairo. The palm trees, orange groves, and fellahin villages along the Nile enchanted Werfel, and he found the quality of the light and the exotic landscape inspiring. An idea for a play that had preoccupied him years before resurfaced in Egypt: a play with Akhenaton, the pharaoh who embraced the Sun God, as its central character. Werfel also pondered the Islamic religion, about which he did not know much: “What is the nature of the Muslim’s fanaticism?” he wrote in his diary. The Muslim “has to observe more prayers, rules, laws, and formulas than the devout person of any other religion!!” He became preoccupied with the figure of the mahdi, the Muslims’ messianic renewer of the world, thinking that it might provide material for a novel. In a small suburban mosque in Cairo he witnessed the ancient, ecstatic dance of the dervishes and was fascinated: “The noble form of the sheik of the dervishes in his blue cape shakes with a sudden convulsion… And suddenly the sheik glides away from his spot with an unspeakably holy grace… Effortlessly the blue one has gained the center. And now he bobs up and down, as if he were not supported by the floorboards but by the waves of a magical sea.”

After a few days, Werfel found the contrast between the upper-class hotel in Luxor, mostly inhabited by British and German tourists, and the alien and mysterious land surrounding it, with its “pitch-black people” and horrifying poverty, hard to endure. Furthermore, he found “this rushing through temples and landscapes boorish and soul-killing.” More and more he disliked being a tourist among other tourists.

|

| |

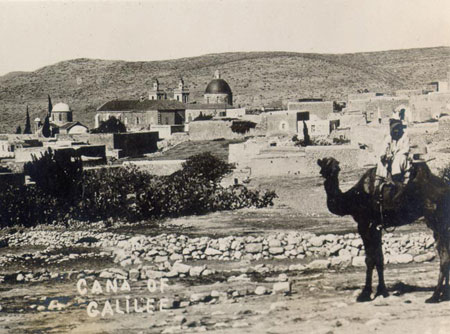

Cana of Galilee |

| |

Alma and Werfel decided to take the train to Palestine. The two weeks that followed were characterized by extreme anxiety and a tumult of emotions, a seesaw of feelings the likes of which Werfel had hardly ever experienced. “From the very first moment, I felt torn,” he noted. “My hand is no longer free. My mind is no longer at peace.” While he had not sympathized much with Zionism in his youth, he now found himself, due to Alma’s Antisemitism which she made particularly plain on this trip as well as her virulent hatred of communism, defending a cause that really was not his. “Those were days of deep anxiety”, he later wrote.

|

|

| |

|

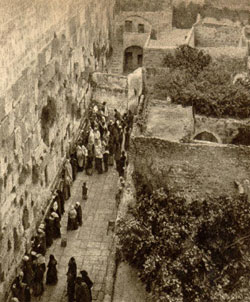

Wailing Wall |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

Apart from side trips to the northern part of the country and to the Dead Sea, Werfel spent most of his time in Jerusalem. He visited the church of Christ’s grave and the Wailing Wall, as well as the Islamic Temple Mount, Mount Moriah of the Old Testament, where Abraham went to sacrifice Isaac, the site of Solomon’s Temple and the Second Temple. He took daily walks through the narrow streets of the Old City, returning over and over again to the places of worship of the world’s three monotheistic religions. He met the Kabbalah scholar Gershom Scholem; talked to physicians, architects, and philosophers, arguing with them about the pros and cons of Zionism; and visited numerous agricultural schools and cooperatives in the countryside surrounding Jerusalem.

“Today I lost my interest in the Jews,” Werfel had noted on board the Vienna, with its passengers bound for Palestine. In reality his alienation from his own Jewishness had begun years ago, long before he met Alma Mahler - who indeed approved of it wholeheartedly. Bar-mitzvah not- withstanding, Werfel had long seen himself as a believer in Christ to whom Judaism had become an alien world, one that even embarrassed him. “What did I have to do with these people,” he argued in an unpublished essay written in 1920, “with this alien world? My world was the great European artists with all their contradictions, form Dostoyevsky to Verdi.”

In Jerusalem, at the source of theology, Werfel searched his memory for the point at which he had become conscious of turning away from the religion of his forefathers. He saw himself at four or five years old, walking to Sunday morning mass with Barbara Simunková; he heard again the solo soprano voice in choir of the Maisel synagogue in Pargue - which had struck him as “mortally indecent” when he was ten, so that the entire Jewish service made him “uncomfortable” and would henceforth seem an embarrassment. He remembered his religious instructors, his later arguments with Max Brod, his meetings with Martin Buber.

The journey through Old Testament lands shocked Werfel into an intense preoccupation with his Jewish origins that went far beyond his admitted interest in Israel’s religion and history. In the months following his return from the Middle East, he spent time almost every day reading about Jewish history, customs, and rituals; he relearned Hebrew, written and spoken, and studied German translations of the books of the Old Testament and the Talmud. |

|