On Alma's tracks in Jerusalem

In 1924 and 1929, Alma and her third husband Franz Werfel travelled to Palaistina-Eretz-Israel which turned out to be an explosive preoccupation for them on both a personal and intellectual level. From the different types of Jewish immigrants on the ship - modern young Zionists as compared with east-European Jews in kaftan and streimel - through the various different approaches to establishing a Jewish life in Palaistina-Eretz-Israel, to the numerous testimonies of Jewish history, the impressions gained on their travels presented a broad panorama of the "condition judaica".

|

| |

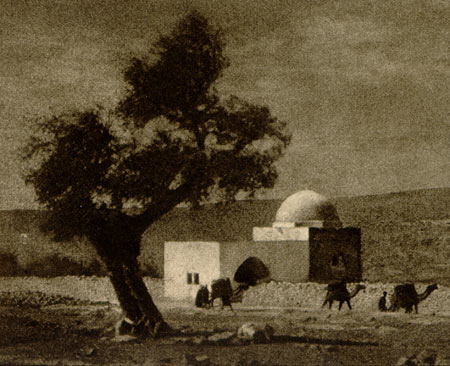

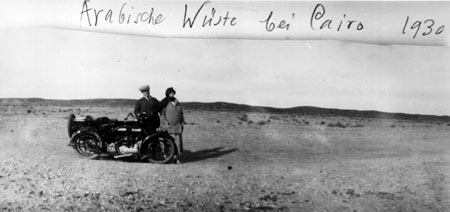

Photographs from Alma's private photo collection |

On these trips, Werfel was confronted with much that was to become a central aspect of his creative output in subsequent years; the history of the Jewish religion, the development of Christianity out of Judaism, the role of religion in history and in the "salvation of the individual" all found their expression in his dramas and novels. All of this confronted Werfel with his own Jewishness and compelled him to plumb the depths of his own relationship with it.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Street of the Chain, the eastern section of David Street in Jerusalem:, one of the main streets in the Old City which runs downhill to the Gate of the Chain, the most important entrance to the Temple Mount |

|

The Western Wall, the most important Jewish religious site located in the Old City, the remains of the great Jewish temple dating from the end of the Second Temple period. The temple itself was thought to be the place where God resides on earth. |

Alma's Journey to the Near East in 1924

"I decided upon the Near East. Ever since he had become well known, Werfel had been urgently invited by the Zionists to visit Palestine. He had never been able to make up his mind to accept, but at the end of that year, while he was in Prague with his family for a few days, I got tickets, started to pack, and welcomed him back with the news that within a week we were leaving.

First, we went to Egypt. We landed in Alexandria, and, in the dining car to Cairo, Werfel tasted all the hors d'oeuvres and arrived at Cairo's Hotel Continental a very sick man. I had to sit up with him all night. But he recovered, and in the morning we set out to conquer this unique city by ourselves, without any guide. We strolled through mosques and bazaars and bought attar of roses, of which Werfel was inordinately fond; we went almost daily to the Opera and heard Aida in the spot where its premiere had taken place in 1871, during the festivities accompanying the Suez Canal opening; we moved to the Mena House, the hotel that faces the Great Pyramid, and spent whole days in the museum. "By now I could serve as a guide to Cairo," l wrote in my diary.

|

We took a trip up the Nile, to Luxor and Karnak on the site of Thebes, capital of the Ancient Empire. We stood in 4000 year old temples, among tokens of the agelessness of civilization; we were overwhelmed by the abundance of nature, by the living fantasy that was Egypt. The only thing we could not stand was the food, which either smelled fishy or was cooked in the monotonous English fashion.

One night while I was still reading, Werfel called to me across the large foyer between our rooms. He came over to sit on my bed, and we had gourmet's fantasies: "Would you like some venison steak now, with cranberries and potato pancakes? Would you like a little roast pork with Sauerkraut and dumplings? Or a beef stew with mushroom sauce?" It went on and on. Finally he got up and went to bed, and we felt well fed and satisfied with our imaginary meal. It was almost as when we were hearing music together, clasping hands and simultaneously feeling the electric shocks of sound. The source of what beauty there is in life does not matter as long as we strongly receive it, feel it, and pass it on!

From Cairo we went to Palestine. Our train reached the border at El Cantara about midnight; it was icy cold, and a gale blew us along the platform as we got out for the strict passport and customs inspection. The Russian Jew who was to help us looked gloomy. We asked why. "Only five Jews today," he explained. "You two, and three others." I said this meant that only four Jews had arrived - because I was a Gentile. "Never mind," he said severely. "You're coming here with Herr Werfel, so you're Jewish." My attempt to talk him out of his chauvinism failed.

Near Jerusalem a gentleman boarded the train who said he had been sent to our assistance by the Zionist Executive. He introduced himself as Herr Seligmann from Germany and rebuked us for arriving later than announced; the "Executive," he said, was pretty angry. Then he sat between us and told us all about his family.

We chatted cozily until the train pulled into the Jerusalem Station. Then Herr Seligmann jumped on the seat, hoisted our suitcases off the rack, and turned out to be a porter of the Palestinian railways. Awaiting us at the Station was the wife of the dean of the university, who wanted to drag us directly to a children's festival. I said, not without a touch of malice, that Werfel could go - had to go, in fact - and I would take our luggage to the hotel and start unpacking. Werfel's face fell, and, tired as he was, he had to watch five hundred Jewish children plant little trees while I took a cab to the Allenby Hotel, the only possible one in those days.

|

|

Our room was wretched. It had no bath, of course, and was lit by a single small electric bulb on the ceiling. With the help of an Arab houseboy I undertook to civilize it a little - which was no easy task, with traces of the last occupants noticeable everywhere. When the last of the dirty handkerchiefs, collars, hairpins, and so forth had been swept from underneath the bed, I went out into the magical Old City and bought a supply of candles and candlesticks and a few Persian rugs, to beautify our pitiful abode."

(from Alma's autobiography „And the Bridge is Love") |

|