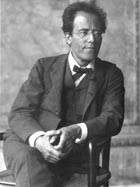

| Life with Gustav Mahler (1901 - 1911) On 7 November 1901, at the house of her friend Berta Zuckerkandl, Alma met celebrated conductor Gustav Mahler who, as Director of the Vienna Court Opera, held one of the most powerful positions in the world of music.  |  |  | | | | | | Alma Schindler, 1900 | | Gustav Mahler en route to the Vienna Court Opera | At the evening gathering, Mahler fell in love with the young beauty, and just a few weeks later, on 28 November, he made her a proposal of marriage. Alma's family attempted to persuade Alma not to enter into the association, since Mahler, 19 years her senior, was considered too old for her, and there were also rumours that he was completely impoverished and suffering an incurable illness. The Jewish origins of the Bohemian composer, who had converted to Catholicism, constituted a further stumbling block.  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Berta Zuckerkandl | | Gustav Mahler, Director of the Vienna Opera | | Alma Schindler, 1900 | On 19 December 1901, Mahler wrote a 20-page letter to Alma, in which he set out to his wife his plan for a future life and requested that she abandon her composition work: "How do you imagine both wife and husband as composers? Do you have any idea how ridiculous and subsequently how much such an idiosyncratic rivalry must end up dragging us both down? How will it be if you happen to be just "in the mood" but have to look after the house for me, or get me something I happen to need, if you are to look after the trivialities of life for me? - Does this mean for you breaking off your own life, and do you think you will have to do without a high point of being which you cannot live without, if you entirely give up your music in order to possess - and also to be - my own?" Alma was confused and wrote in her diary, "He thinks nothing at all of my art - and thinks a great deal of his own - and I think nothing of his art and a great deal of my own. That's how it is! Now he constantly talks of preserving his art. I can't do that. It would have worked with Zemlinsky, because I empathize with his art - he is a brilliant chap." However, on 23 December the couple became engaged, and on 9 March 1902, Alma and Gustav Mahler married in Vienna at the Karlskirche. Both Mahler's friends and many from their circle of acquaintances reacted uncomprehendingly to the marriage. Bruno Walter, conductor at the Opera House and Mahler's closest confidant, wrote: "Mahler is 41 and she 22, she is a celebrated beauty, used to a glamorous social life, while he is so unworldly and fond of being alone ..."

The couple moved into an apartment near the Opera House. Their household included two maids and an English governess for their daughter Maria, who was born on 2 November 1902. However, life together with Mahler was completely different from the varied and gregarious life to which Alma had been accustomed at her parents' house. Mahler hated socializing, and attached great importance to a regular daily routine in order to manage his workload. Alma soon felt isolated, felt herself to have been degraded to the level of housekeeper, and was bored. The feeling of inner emptiness was not changed either by the birth of the couple's second daughter, Anna Justina, who was born on 15 June 1904 and nicknamed "Gucki" ("peek") because of her expressive eyes.  |  |  | | | | | | Alma in 1904 with her newborn daughter Anna ("Gucki") | | Alma in 1905 with Gustav Mahler (centre) and daughters Maria and Anna | In the person of his wife, Mahler missed having a companion with whom to share life. The conflict between them worsened when she allowed herself to succumb to an impetuous flirtation with his colleague Hans Pfitzner. With the knowledge and approval of Mahler, Alma had also been getting together again with Zemlinsky in order to make music with him. However, Zemlinsky refused to begin teaching her again. In July 1907, the couple's daughter Maria, who was just five years old, died of diphtheria. For Mahler, the death of his beloved child marked a figurative caesura in his life, and increased the gulf between him and Alma. Moreover, at a routine examination, Mahler was found to be suffering from a heart defect which severely restricted his activities. In the Viennese press there were repeated criticisms of Mahler's leadership style at the Opera House, which finally led to his withdrawal from the Viennese music scene. In December 1907, he took on an appointment with the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, to which Alma accompanied him. While Mahler celebrated his first major success with the performance of Wagner's Tristan and Isolde, in New York too, Alma felt isolated and alone. In the six months which the couple subsequently spent back in Europe, Alma spent most of her time at convalescent spa resorts and lived apart from her husband. It can be seen from letters that, during this time, Alma at least suffered a miscarriage or had an abortion. In May 1910, Alma went with her daughter Anna to the spa town of Tobelbad, a small upcoming resort in Styria. After eight years of disappointment, Anna now consoled herself for her years of deprivation in the person of a young architect named Walter Gropius, who was later to become a leading figure in modern architecture through the Bauhaus movement. After all the years with Mahler which, for Alma, were characterized by deprivation and asceticism, her pent-up longing to be taken seriously as a woman now exploded within her. The two lost themselves in unrestrained nights of passion.  |  |  |

Above: Alma out walking with Gustav Mahler in Toblach (1909/1910)

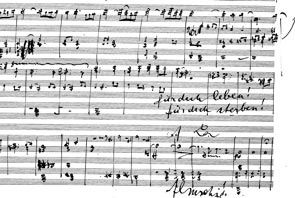

Left: Young architect Walter Gropius | The affair came to light when Gropius "mistakenly" addressed to Gustav Mahler a love letter intended for Alma. Despite talking through the situation, Alma however continued her relationship with Gropius in secret. Mahler's 10th Symphony was created in the light of this discovery, and the manuscript reveals an abundance of personal entries documenting how Mahler was going through the hardest crisis of his life at the time: "You alone know what it means. Oh! Oh! Oh! Farewell my lyre! Farewell, farewell. Farewell" and "To live for you! For you to die! Almschi!".  |  |  | | | | | | The manuscript of Mahler's 10th Symphony

bearing the handwritten notes:

"To live for you! For you to die! Almschi! | | Gustav Mahler in 1910 on the ship to New York | Mahler was recommended to get in touch with Sigmund Freud, who saw him in August 1910 in the Dutch seaside resort of Leiden. Little is known about this meeting, which only lasted just under four hours. There are scarcely any documents relating to the brief session of analysis, but Freud evidently analyzed the essence of the relationship, which was marked by a reciprocal longing for a father/mother substitute.  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Marie Mahler,

Mahler's mother | | Gustav Mahler 1907 | | Alma Maria,

Mahler's wife | To his student Marie Bonaparte, Freud said the following: "Mahler's wife Alma loved her father Rudolf Schindler and could only seek out and love his type. Mahler's age, of which he was so afraid, was precisely what made him so attractive to his wife. Mahler loved his mother and sought her type in every woman. His mother was troubled and full of suffering, and subconsciously he wanted this also from his wife Alma." With this insight, Freud granted a licence to commit incest, and thereby brought the couple some final happy months together. However, Alma was outraged when, shortly after Mahler's death, Freud blithely sent her the invoice for this brief session of analysis.  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Mahler 1911 | | Sigmund Freud

analyzed the marriage | | Alma 1909 | Mahler now began focusing intensively on his wife Alma, for instance dedicating his 8th Symphony to her, the premiere of which, on 12 September 1910, was to become his greatest musical triumph. Mahler also had five of Alma's Lieder compositions published in the same year, with premieres in Vienna and New York. Shortly before she accompanied her husband to the USA for several months, Alma travelled to Paris in order to meet up with Walter Gropius once again. On his last trip to the USA, Mahler fell seriously ill. On 21 February 1911, he conducted his final concert in New York, and then Alma travelled with her husband back to Europe. The couple reached Vienna on the evening of May 12. Gustav Mahler died on 18 May 1911 at around midnight, aged nearly 51. He was buried in Grinzing Cemetery alongside his beloved daughter Maria Anna.  |  |  |  | | | | | | | The last photograph of Mahler, on the crossing from NY to Europe, 1911 | | Mahler's death mask, taken by Carl Moll | | | | | | | "This man possessed of such wealth, who has plunged us into the profoundest sorrow: bereft of the divine presence of Gustav Mahler, we are left for a lifetime with the indestructible paragon of his work and creative endeavours." (Wreath ribbon of Arnold Schönberg and several of his students)

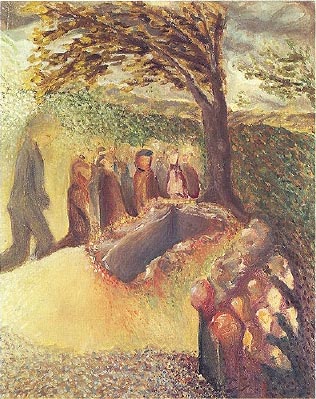

In accordance with Mahler's wishes, the burial was devoid of any ceremony, and thus his gravestone bears only his name. His body was laid out in a small chapel just large enough to accommodate the coffin and the first few wreaths. The number of wreaths was indeed so great that the others had to be lined up along the entire path to the grave of his young daughter, for he wished to be laid to rest beside his child. "The grieving Fourth Balcony of the Viennese Court Opera in ineffaceable recollection - Figaro, Fidelio, Iphigenia, Tristan."  |  | | | | | Arnold Schönberg: The Burial of Gustav Mahler

(22 May 1911 in Vienna), Oil on canvas | | | | | Mahler's body was taken from the chapel to the grave amid heavy rain, and as soon as the funeral party arrived at the grave, the coffin was lowered without any further ceremony. The still large crowd in attendance, numbering several hundred, dared scarcely speak. The rain had stopped, and a rainbow in seven colours shone in the sky, while the song of a nightingale penetrated the silence. Then the clods of earth fell, and it was all over. > next: Heaven and hell (1911 - 1917)

< back: The most beautiful girl in Vienna (1879 - 1901) | |