| "Man-child" Franz Werfel (1917 - 1938) During the First World War, lively social activity carried on at Alma's salon in Elisabethenstrasse. Composers, writers, painters, conductors, actors and academics regularly gathered at her house. It was an elite group of intellectuals who were inspired, promoted or criticized by her - her manner of looking at such geniuses was penetrating and challenging.  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Alma the Muse | | Alma Mahler-Gropius | | Gropius as a soldier | On 14 November 1917, writer Franz Blei brought Franz Werfel, who was just 27 years of age, to an evening gathering at Alma's salon. Two years previously, Alma had set his poem "Der Erkennende" to music, but had not previously had a personal meeting with Werfel, who was until that time mainly known as a lyricist. At first she did not find Werfel physically very attractive, and was bothered by the fact that he was Jewish; "Werfel has bow legs and is a fat Jew with thick lips and oozing slitty eyes! But the more he presents of himself, the better he gets." Unlike Gropius, who had little interest in music, Werfel however shared Alma's enthusiasm. In the following weeks, he visited her more frequently in order to make music with her. Franz Werfel was a well-known Expressionist lyricist when he first met Alma. Night after night he used to trawl through the bars and cafés of Vienna with Ernst Polak, Alfred Polgar and Robert Musil, but all this was soon to change. Werfel described his beloved as "guardian of the fire", who demanded a daily quota of lines from him and urged him to implement the creative ideas which he had previously not had the energy to fulfil. While she was still married to Gropius, in early 1918 Alma became pregnant by Werfel. The child was born prematurely, since Werfel was unable to control his insatiable lust and forced it out of his beloved's womb in a veritable bloodbath one night in Breitenstein. Baby Martin suffered from hydrocephalus and died ten months later, a consequence of Werfel's "depraved seed", as Alma described it. Since Gropius had by chance overheard a telephone conversation between his wife and Werfel, he was forced to acknowledge that he had not been the child's father.  |  |  | | | | | | Alma and Werfel, 1919 | | Alma's house in Breitenstein am Semmering | Werfel saw in Alma his saviour, a goddess whom he was permitted to worship, and described her as "one of the few magical women who exist". She allocated him the isolated house in Breitenstein am Semmering as a work base. In any event, for Alma, her marriage to Gropius was a mixture of social convention, inner emptiness and disorientation; on 11 October 1920 they divorced. For a long time, the couple were in dispute over custody of their daughter Manon. In a letter to Alma at the time when they were still married, which he wrote to her on 18 July 1919, Gropius soberly noted:  | | | | Alma with Walter Gropius and their daughter Manon, 1918 |  | | | | Walter Gropius | "Our marriage was never a marriage. There was no woman in it. For a brief time, you were my magnificent beloved and then away you went, unable to outlast with love and mildness and trust the affliction borne of the withering effects of war - that would have been a marriage." Although the relationship between Werfel and Alma Mahler was already public at this time, Gropius took the blame upon himself for the failure of his marriage. In a piece of farce fit for the theatre, he let himself be caught in flagranti with a prostitute in a hotel room so as to bring about a quick divorce.  |  |  | | | | | | Franz Werfel and Max Reinhardt | | Alma Mahler-Gropius 1920/21 | Alma had been living together with Franz Werfel since back in 1919. The relationship became public when, in mid April 1920, Max Reinhardt invited Werfel to read from his new trilogy of verse "Spiegelmensch" (Mirror Man) at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin, a great honour for Werfel. Alma accompanied Werfel - eleven years her junior - to Berlin, and did not leave his side; the social sensation was impeccable.  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Composer

Ernst Krenek | | Anna Mahler in around 1920 | | Krenek and Anna in the garden at Casa Mahler | In 1922, Alma's daughter began a relationship with composer Ernst Krenek, who only met the once celebrated Viennese beauty when she was already in her early forties. In his memoirs "Im Atem der Zeit" (In the Breath of Time), he painted a very malicious picture of her:  |  | | | | | | Alma in front of the Campanile in Venice | "A magnificently tarted-up battleship. - She was accustomed to wearing long, flowing garments in order not to show her legs, which were perhaps a less remarkable detail of her physiognomy. Her style was that of Wagner's Brunhilde transported into the atmosphere of Johann Strauß's Fledermaus." Krenek was impressed by Alma's inexhaustible and indestructible vitality: "She actually had what it takes to turn life into a vertiginous carousel." Alma invited Anna and Ernst Krenek to the best restaurants in Berlin, where she ordered "sophisticated, complicated and clearly expensive dishes and above all very rich beverages of all types". On these occasions, Krenek noticed that food and drink were the basic elements of her strategy aimed at "making people helpless subjects of her power". She indulged and bewitched her guests and was on top form "when the senses and reason of her entourage were simultaneously befuddled and aroused." And: "Sex was the main topic of conversation, and mostly the sexual habits of friends and enemies were analyzed vociferously, with Werfel attempting to introduce a serious and intellectual note by festively spreading the word about global revolution." In the early 1920s, in addition to her apartment in Elisabethenstrasse in Vienna and her house on the Semmering, Alma acquired a further residence, a small palazzo in Venice - Casa Mahler - not far from the Church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari.  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Alma

la Divina | | Alma with Franz Werfel and Carl

and Anna Moll, 1925 | | "Casa Mahler" (left), not far from Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari | | | | | | |  |  |  | | | | | | Alma with Franz Werfel and Manon on St Mark's Square in Venice, 1923 | | Anna Mahler in Santa Margherita, 1920s | Getting hold of money

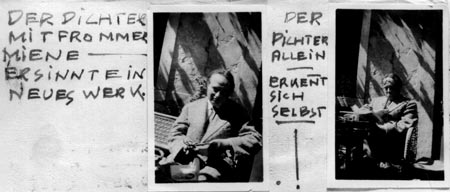

There was scarcely anything left of Mahler's estate, since in 1914 Alma had invested a large part of it in war bonds. The remainder was eaten up by inflation in the 1920s. Moreover, since during this time, Mahler's symphonies were played only occasionally, income from royalties was too low to finance the opulent lifestyle which Alma Mahler led. Alma commissioned her son-in-law, Ernst Krenek, to transcribe the fragment of Mahler's unfinished 10th Symphony into a completed piece of work. Krenek however refused to accede to this sacrilegious request and only edited the almost-finished movements of the Adagio and Purgatorio, which were premiered on 12 October 1924 at the Vienna State Opera under the baton of Franz Schalk.  |  |  | | | | | | Alma and Franz Werfel in Trahütten, 1925 | | Gustav Mahler's death mask | Parallel to this, Alma arranged for publication by the newly-established Paul Zsolnay Verlag of a collection of Mahler's letters, as well as a facsimile of his 10th Symphony, the pages of which however bore very personal handwritten notes, "the cry of a tortured soul", in which Mahler expressed his desperation over Alma's affair with Walter Gropius - "raptures of a desperate passion directed at Alma, demented utterances of a man battling with death and who was scarcely aware of the object of his writing" (Krenek). At the same time, however, Alma also published five of her own hitherto unpublished songs, and Universal Edition released a further edition of the "Four Lieder" which had previously been published in 1915 with the support of Gustav Mahler. Nonetheless, Franz Werfel was cultivated to become the big earner in the Mahler-Werfel household. In April 1924, "Verdi - Roman der Oper" (Novel of the Opera) was published by Zsolnay Verlag, and it established Werfel's name as a novelist; within just a few months, the book sold more than 20,000 copies. Alma had given Werfel substantial support in his work and provided critical accompaniment to his progress, since she was surely aware that a novel can earn more money than poems and short stories, and that it had to be "as good as one of the classics" but at the same time suitable for sale on train-station newspaper stands.  | | | | "The poet with the pious look - is devising a new work. The poet alone -

recognizes himself!" (from Alma's Venetian photo album) | Alma's efforts to obtain money were quickly successful; as early as 1925 she was able to support Alban Berg in publication of his opera "Wozzeck". In gratitude, he dedicated the opera to her. In 1926, Werfel was awarded the Grillparzer Prize by the Austrian Academy of Sciences, and in Berlin, Max Reinhardt performed his play "Juarez and Maximilian".  |  | | | | | | Franz Werfel 1930 | At the age of 50, on 6 July 1929, Alma finally married her "man-child", Franz Werfel, Jewish poet and author of novels and successful theatre plays, who at the time was among the most read authors in the German language. This was her third marriage. Together, the two commuted with their daughter Manon between the "Casa Mahler" in Venice and their house on the Semmering. In January 1924, Alma confided in her diary: "I don't love him any more. My inner life no longer connects with his. He has dwindled away once more to become that small, ugly, adipose Jew of my first impression." Alma's marriage was also a reaction to her advancing age and her physical decay; neither, since her youth, had she lived alone, and she feared no longer finding a life partner. However, the two spent lengthy periods apart. Alma travelled alone to Venice, while Werfel spent his time on the Semmering or in Santa Margherita Ligure in the province of Genoa in order to work on his novels there. Moreover, he did not feel at home in the ostentatious villa on the Hohe Warte in Vienna, and on top of all this, differing political opinions also contributed to the widening gulf between them. Amid a climate of growing political radicalization in Austria and neighbouring Germany, Alma's notorious anti-Semitism grew. For instance, she made it a condition that Werfel would have to abandon his Jewish faith before marrying her. Werfel complied with her request, but just a few months later, without Alma's knowledge, returned to Judaism. Alma had a positive view of the Nazis, and following the suspension of Parliament by Engelbert Dollfuss, in the civil war of 1934 she was on the side of the Austro-fascists. The Spanish Civil War was a further bone of contention between the pair since Alma sided with Franco, while Werfel supported the Republican side.  |  |  | | | | | | Oskar Kokoschka: Alma

Mahler as "la Gioconda"

(1912, oil on canvas) | | Alma with Franz Werfel in the salon of their villa on the Hohe Warte, with Kokoschka's Alma portrait on the wall and one of his fans, 1931 | "People are starving in jail, but the Werfels are living a life of ease and currying favours. The embodiment of human filth," commented the Brünner Arbeiterzeitung on Werfel's woolly political attitude - which was characterized by political naivety and the influence of Alma - when in 1935 he went on excursions with Schuschnigg and his wife in a limousine provided by Benito Mussolini. The 25th anniversary of Gustav Mahler's death took place under the honorary protection of Chancellor Schuschnigg, and in 1937, Werfel was even awarded the "Austrian Cross of Merit for Arts and Sciences". Since the beginning of the 1930s, Alma's villa on the Hohe Warte had been frequented by an increasing number of guests who shared Alma's political views. Alongside Austrian Chancellor Schuschnigg there was also fascist putschist Anton Rintelen, and 37-year-old theology professor and priest Johannes Hollnsteiner, who perceived in Hitler a "new Luther". He fell in love with the 50-year-old Alma, and the two ended up having an affair, for which Alma even rented a small apartment in order to be able to meet in secret with her lover. In 1935, Manon suddenly died of polio, aged just 19, her mother having attributed her Anglo-Saxon beauty to the fact that her father, Walter Gropius, was "Arian". Her funeral was a major social event in Vienna; Hollnsteiner gave the eulogy, while Alban Berg dedicated his Violin Concerto to her - "In memory of an angel".  |  | | | | | Alma with Johannes Hollnsteiner and her daughter Manon in Vienna, 1933 | | "She blossomed like a wondrous flower. She passed through the world pure as an angel. She was joy and love to so many. For those to whom she was closest however, she was sunshine and joie de vivre. She has gone over to His Kingdom; at the festival of love and resurrection, the divine conqueror of death and adversity has fetched her home into the Kingdom of which it is said: 'No eye has seen and no ear has heard what God has prepared for those who love him.' "

(from the eulogy by Johannes Hollnsteiner) The palatial villa on the Hohe Warte soon became for Alma an emotional burden, since Manon had died there. In any case, Werfel preferred to work in hotel rooms outside Vienna. On 12 June 1937, Alma gave a farewell party at the villa, at which all Vienna was present, including Bruno Walter and Alexander von Zemlinsky, Ida Roland, Carl Zuckmayer, Egon Wellesz, Ödön von Horváth, Siegfried Trebitsch, Arnold Rosé, Karl Schönherr, Franz Theodor Csokor and many more. A Schrammel band played melancholic Viennese Volkslieder, and for many the mood in the air evoked the ending of an era. Following the Agreement between Hitler and Schuschnigg of 11 July 1936 by which, in return for Germany's recognition of Austria's sovereignty, an amnesty was to be given to Austrian Nazis, worries about the future of this small country grew.  |  |  | | | | | | Alma and Franz Werfel, 1937 | | Alma's villa on the Hohe Warte | The party began at 8 pm and lasted until 2 pm the next day. Franz Werfel ended up falling drunk into the garden pond, and Carl Zuckmayer spent the night in the dog kennel. > next: Emigration (1938 - 1945)

< back: Heaven and hell (1911 - 1917) | |