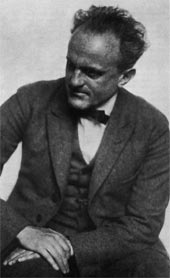

An unusual testimony about Kammerer's scientific attitudes came from Alma Mahler. In 1911 and 1912, just after the death of Mahler, Alma worked briefly as an unpaid laboratory assistant to Kammerer, and described this experience in her autobiography, „And the Bridge is Love“: "To this end I was to teach them (praying mantids) a habit a futile endeavor, since you could not teach the little beasts a thing. I was to feed them at the darkened bottom of their cage, but they preferred to eat high in the sunlight and firmly refused to change this sensible attitude for Kammerer's sake. I kept records, very exact records. That, too, annoyed Kammerer. Slightly less exact records with positive results would have pleased him more." Way back in the 1920's, Paul Kammerer was the most famous biologist in the world. He was hailed by The New York Times as the next Darwin. Paul Kammerer was born in Vienna on August 17, 1880. When he reached adulthood, he enrolled in the Vienna Academy to study music. The piano was his instrument of choice. Yet he ended up graduating from the university with a degree in biology.  |  |  | | | | | The biologist Paul Kammerer | | The last specimen of the midwife toad with the famous rutting weals | Almost all of Kammerer's experiments involved forcing various amphibians to breed in environments that were radically different from their native habitat. Kammerer experimented with the cave-dwelling newt Proteus. Proteus is totally blind and only has rudimentary eyes that are buried deep beneath the skin. He found that exposing the blind newts to ordinary light only produced a black pigment over the eye and sight never developed. Yet, when Proteus was raised under red light, Kammerer was able to produce specimens with large, perfectly developed eyes. Kammerer was studying another amphibian, the midwife toad, Alytes obstetricians. Unlike most other toads and frogs that mate in water, the midwife toad breeds on dry land. Kammerer decided to force the midwife toad to copulate in water. He was able to breed six generations of the toad until the lineage died out. Even more surprising was that the midwife toad had developed nuptial pads. Nuptial pads are black calluses containing very minute spikes that develop on the male during mating season. This allows the male to hold on tight while breeding takes place in the slippery water. Since the midwife toad breeds on dry land, it does not need or possess these pads. With each generation, the nuptial pads became more prevalent. Kammerer suggested that, once again, this provided evidence that inheritance of acquired characteristics had taken place. Almost instantly Kammerer found himself in the middle of a worldwide controversy. Many scientists sided with him, while others thought that his findings were ludicrous. World War I devastated Austria and the onset of the great depression had left Kammerer very poor. He was forced to abandon his research and preserved his last few specimens in jars of alcohol. Kammerer was forced to embark on the profitable lecture circuit. One of his stops was at Cambridge in England in 1923. He brought with him his last remaining specimen of the midwife toad (the rest were lost during the war) - a fifth generation male. A large number of scientists attending the conference examined this specimen. The nuptial pad was clearly visible (the other had been removed to prepare biological sections), and no one questioned its authenticity. Kammerer continued to tour the United States. He was a sensation. Newspapers exaggerated his claims, and he created ever increasing sensation. That was until August 7, 1926. On this date, an article appeared in the British journal Nature. The author, Dr. G. K. Noble, Curator of Reptiles at the American Museum of Natural History, claimed that the nuptial pads on the midwife frog were faked. They were, with almost complete certainty, India ink! The nuptial spines could not be located, either. Shortly thereafter, on September 23, 1926, Kammerer took a walk in the Theresien hills of Austria and chose to end it all. He put a bullet through his head. Scientists had examined the toad specimen just three years prior at Cambridge and no one had questioned its authenticity (they only questioned Kammerer's theories), even after handling and microscopically examining the toad in question. Even if the darkened pads were actually injected ink, many claimed to have clearly seen the spines. Also, Kammerer had resigned from his position at the institute several years prior to the final examination and apparently did not have ready access to the preserved toad. Yet, the ink appeared to have been injected just several days prior to this crucial examination. Some have suggested that the ink was injected after its examination at Cambridge to preserve a rapidly decaying specimen. Or, the ink may have been injected to make the nuptial pads more readily visible. And, even quite possibly, the ink was injected with the sole purpose as to discredit Kammerer. Photographs of the suspected midwife toad still exist and the spines on the supposed nuptial pads are clearly visible. Some have suggested, including Noble in his 1926 article, that Kammerer simply used the nuptial pads of a similar frog, such as Bombinator maxima. Others have argued that this substitution was impossible, as too many people were involved in the preparation of the photographic plates. Also, there was no record that the University had ever had a single specimen of Bombinator. This controversy over one toad cost Kammerer his reputation and, ultimately, his life. Were Kammerer's experiments legitimate? Or were they a fraud? Was Kammerer framed? Or did a helping hand - maybe a woman - try to help him...? We will never know. |