| Alma the composer

During her active period as a creative artist, Alma composed over one hundred Lieder, various instrumental pieces and the beginning of an opera. However, only sixteen Lieder from her body of work have survived. The remaining compositions were lost during the Second World War.  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Alma 1900 | | Alma 1909 | | Alma 1900 | In 1910, Alma's husband Gustav Mahler published five Lieder with Universal Edition which Alma had composed between 1900 and 1901. Following the grave marital crisis which followed Alma's affair with Walter Gropius, as if he had a bad conscience, Mahler suddenly turned his attention to these youthful compositions, and even proposed that they jointly rework them. In the same year, he had the following five Lieder printed and premiered in Vienna and New York:

- Die stille Stadt (The Silent City), text by Richard Dehmel

- In meines Vaters Garten (In my Father's Garden), text by Otto Erich Hartleben

- Laue Sommernacht (Balmy Summer's Night), text by Otto Julius Bierbaum

- Bei dir ist es traut (With You It is Pleasant), text by Rainer Maria Rilke

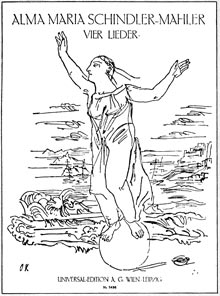

- Ich wandle unter Blumen (I Stroll Among Flowers), text by Heinrich Heine  |  |  | | | | | | First publication of Alma's Lieder, published in 1910 by Gustav Mahler | | Vier Lieder, 1915, with the title page Fortuna by Oskar Kokoschka | In 1915, Alma Mahler-Werfel published four further Lieder, from the period between 1901 and 1911. The title page is decorated with Oskar Kokoschka's lithograph Fortuna:

- Licht in der Nacht (Light in the Night), text by Otto Julius Bierbaum

- Waldseligkeit (Woodland Bliss), text by Richard Dehmel

- Ansturm (Storm), text by Richard Dehmel

- Erntelied (Harvest Song), text by Gustav Falke In 1924, five more Lieder were published:

- Hymne (Hymn), text by Novalis

- Ekstase (Ecstasy), text by Otto Julius Bierbaum

- Der Erkennende (The Recognizer), text by Franz Werfel, composed 1915

- Lobgesang (Song of Praise), text by Richard Dehmel

- Hymne an die Nacht (Hymn to the Night), text by Novalis In 2000, two posthumous Lieder of Alma were published:

- Kennst du meine Nächte (Do You Know My Nights), text author unknown

- Leise weht ein erstes Blühn (Softly Drifts a First Blossom), text by Rainer Maria Rilke Alma in the music of other composers MAHLER Fifth Symphony (Love letter to Alma)  |  | | | | | Mahler and Willem Mengelberg, 1906, at the Zuiderzee in Holland | | The Adagietto in Mahler's Fifth Symphony is a musical homage to Alma. In the score which Mahler gave his friend, conductor Willem Engelberg, Engelberg has made the following annotation: "This Adagietto was a declaration of love to Alma! In place of a letter, he sent her this in manuscript form, not adding a further word. She understood and wrote to him telling him to come!!! They both told me this. WM" The Adagietto also became world famous as the leitmotiv in Visconti's Death in Venice. The Funeral March from the Fifth Symphony exists as played by Mahler himself on a pianola – piano rolls (original recordings) Sixth Symphony (the "Alma theme")

Gustav Mahler's Sixth Symphony in A Minor from 1904 is one of his darkest and most violent works. For a long time, it was rejected even by Mahler's champions as "too negative", but today, over 60 recordings of the composition are in existence. Mahler commenced work on the Symphony in summer 1903 in Maiernigg on the Wörthersee, where he was spending the holidays with his wife and little daughter Maria Anna. Alma reports that at the time he was in good spirits: "He played a great deal with the child, whom he dragged around and lifted up so as to dance and sing with her. He was so young back then, and untroubled."  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Maria Anna, 1906 | | Mahler's villa in Maiernigg | | Alma, 1905 | On 15 June 1904, Alma gave birth to her second daughter, Anna Justine, and travelled to see her husband. "The summer was beautiful, free of conflict, happy," she records in her memoirs. Mahler completed his Sixth Symphony and added three more Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children) to the two already existing. At the end of the holidays, he played the Symphony to his wife. "We used to go arm in arm up to his little forest hut once again, where we were undisturbed in the middle of the wood. The whole thing was always in a great festive spirit." Directly following on from this report, Alma made the following remarks: "After he had conceived the first movement, Mahler came down out of the forest and said: 'I've tried to capture you in a theme – as for whether I've succeeded, I don't know. You will have to tolerate it.' It is the great, rousing theme of the first movement."  | | | | The "Alma theme" in the first movement of Symphony No. 6 "In the third movement (the Scherzo), he evokes the arrhythmic playing of the two young children, running unsteadily through the sand. Spine-chillingly, these children's voices become ever more tragic, and by the end, a fading little voice is left whimpering." |  |  | | | | | | Mahler and daughter Maria | "In the last movement, he evokes himself and his downfall or, as he later said, that of his hero. 'The hero, who suffers three blows of fate, the third of which fells him like a tree.' These are Mahler's words. No work flowed so directly from his heart as this one. At the time we both cried. So deeply did we feel this music, and the presentiment it betrayed. The Sixth is his most personal work of all and a prophetic one too. Both with the Kindertotenlieder and the Sixth Symphony, he 'set his life to music anticipando'. He too was dealt three blows of fate, and the third felled him. Back then, though, he was cheerful, aware of the greatness of his work, and his branches were in full leaf and blossom."  |  | | | | | Mahler with his two daughters in Maiernigg, 1905 | | In this context, it is telling that, after the final rehearsal for the premiere in Essen in May 1906, Mahler was utterly shaken. He sobbed, wrung his hands, and lost his composure. According to Alma, no other work touched him so deeply on first hearing it. In the concert, he is alleged to have conducted the Symphony "almost badly", "because he was ashamed of his agitation and was afraid that he might lose control of his emotion while conducting. He did not wish to let slip the truth of this most dreadful last anticipando movement!" It would appear as if Mahler indeed had a foreboding of the tragic events which would befall him and his family in 1907: the death of his older daughter, his resignation from the Vienna Court Opera, and above all the diagnosis of his heart condition.

Eighth Symphony (dedicated to Alma)

The Eighth Symphony, which Gustav Mahler dedicated to his wife Alma, the symphony with the most massive orchestration (three choirs, a children's choir, vocal soloists, and extended orchestra), giving it the epithet "Symphony of a Thousand", ends with the Faust chorus: "Alles Vergängliche ist nur ein Gleichnis; Das Unzulängliche, hier wird's Ereignis: Das Unbeschreibliche, hier ist's getan: Das Ewig-Weibliche zieht uns hinan." ("All that is transitory is but a metaphor. Here insufficiency becomes event. The indescribable, here it is done. The eternal feminine draws us on.")

|  |  | | | | | | Poster for the premiere

of Symphony No. 8

in Munich | | Gustav Mahler with friends in Munich in

September 1910, at the time of the premiere

of his Eighth Symphony | The overwhelmingly successful premiere on 12 September 1910 in Munich marked a crowning conclusion to his artistic life. It was the last of his works which Mahler himself presented to the world from the concert podium. When he died eight months later, on 18 May 1911, he left behind two unpublished compositions: Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth), and the Ninth Symphony, as well as a manuscript with a draft for a tenth symphony. The rumours initially circulating about the draft of the Tenth Symphony were contradictory, and one can presume that none of those who commented on the Tenth Symphony had the opportunity to subject the manuscript to closer scrutiny. Alma Mahler kept the draft of the Tenth Symphony under lock and key, and as a result, for a while it was paid no further attention. In the play Alma, the "Eighth" is allocated to Oskar Kokoschka, Alma's wildest and most desperate lover. The Veni Creator spiritus appears in various places to herald the Alma doll, while Kokoschka's wounding and her arrival is accompanied by the resplendent choral passage. Symphony No. 10 (Alma's infidelity)

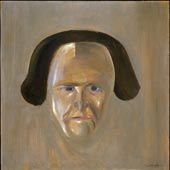

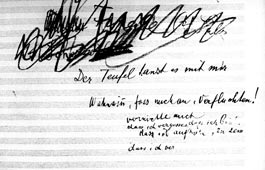

The mystery of Mahler's "last" symphony has always captivated. "It looks," conjectured Arnold Schönberg, "as if perhaps something is being said to us in the "Tenth" which we are not yet meant to know." He was thereby paying homage to the aura of that ominous number, at which so many leading symphonists, including Beethoven and Bruckner, had failed. Neither did Mahler succeed in completing a tenth symphony. Along with Schubert's "Unfinished" Symphony, his last work shares the character of a fragment; and Mahler's "Tenth", like Bruckner's "Ninth" and Mozart's Requiem, shared the fate of having been literally thwarted by the composer's death.  |  |  | | | | | | Arnold Schönberg: Portrait of Gustav Mahler (1910) | | Handwritten notes by Mahler on the score of his Tenth Symphony: "The Devil is dancing with me .... Madness, take hold of me, accursed! Destroy me .... so that I forget that I am! So that I stop being .... that I disapp ..." | The manuscripts for the Tenth Symphony came into being between 3 July and 3 September 1910. Mahler spent these weeks in his holiday home near Toblach in South Tyrol. During this summer, his compositional sensitivities were disrupted by events of profound, existential significance, for due to a blunder (or deliberate indiscretion), Mahler learned of the affair which his wife Alma had been having with architect Walter Gropius since the beginning of June. The revelation abruptly destroyed for him all familial security. He was henceforth tortured by fears of loss, and indeed, as we now know, this was by no means without reason, for despite Mahler having the matter out with Gropius, Alma secretly continued the intimate relationship. In order to overcome the direct psychological consequences of the marital crisis, at the end of August Mahler travelled to Leiden in Holland, where he sought advice through therapy sessions with Sigmund Freud. The consultation lasted no more than four hours, and nevertheless was a resounding success.  |  | | | | | Alma's father,

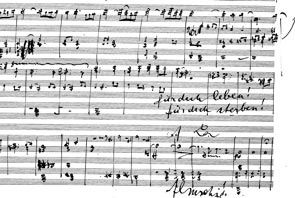

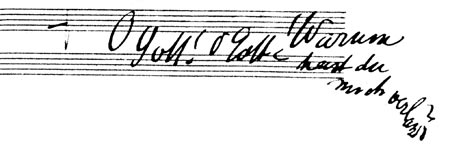

Emil Jakob Schindler | | In a letter to his pupil Marie Bonaparte, Freud commented on his diagnosis as follows: "Mahler's wife Alma loved her father Rudolf Schindler and could only seek out and love his type. Mahler's age, of which he was so afraid, was precisely what made him so attractive to his wife. Mahler loved his mother and sought her type in every woman. His mother was troubled and full of suffering, and subconsciously he wanted this also from his wife Alma." By this analysis, Freud granted an implicit licence to commit incest, thereby blessing the couple with their last happy months together. However, Alma was outraged when, shortly after Mahler's death in May 1911, Freud unabashedly sent her the bill for this brief session of analysis in Leiden. Alma's foreword to the first facsimile edition of the Tenth Symphony of 1924 begins with a confession: "... While I initially considered it my absolute right to keep the treasure of the Tenth Symphony hidden, I now know it is my duty to reveal to the world the last thoughts of the master. The sole proper form of publication for the Tenth Symphony could only be a facsimile. It proclaims not only the last music of the master, but it shows in the impassioned strokes of his handwriting the enigmatic self-image of the person with perpetuating effect. Some will read in these pages as if in a book of magic, while others will find themselves faced with magic symbols to which they lack the key; none will escape the power which continues to emanate from this handwritten music and scribbled verbal ecstasies." Mahler recorded in writing on the score his desperation over his marital crisis:  |  | | | | | "To live for you! To die for you! Almschi! | | Have mercy! Oh God! Oh God! Why hast Thou forsaken me?" "The Devil is dancing with me .... Madness, take hold of me, accursed! Destroy me .... so that I forget that I am! So that I stop being .... that I disapp ... You alone know what it means! Oh! Oh! Oh! Farewell my lyre! Farewell ... Farewell .... Farewell ... well .... Oh, oh." This first facsimile edition was not the only effort by Alma in connection with publication of the Tenth Symphony. In 1924, she consulted composer Ernst Krenek (her son-in-law) with regard to possible completion of the manuscript. He consented, but restricted himself to completing a fair copy of the Adagio (first movement) and a score of the Purgatorio (third movement) which could be performed. As a wily businesswoman, Alma had had the idea, recalled Ernst Krenek, of "adding a tenth to Mahler's nine symphonies, for it appeared to be a simple matter of arithmetic that ten symphonies would be more profitable in concert programmes than nine". However, he decided that he could only edit the sections Adagio and Purgatorio, and would not touch the remaining three movements: "It would have required the shameless temerity of a unspeakable barbarian to attempt to orchestrate these passionate scribblings of a dying genius. Alma was extremely disappointed and disgruntled when I told her how things were. I am glad that I stood firm and did not even dream of assisting in what would have been a vile deception." Arnold Schönberg also refused to make an attempt at completing the work, and while Alban Berg was willing to do so in 1924, because of Schönberg's negative stance he did not dare; similarly, neither Webern nor Shostakovitch showed any interest in such a task.  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Ernst Krenek | | Arnold Schönberg | | Alban Berg | As for how Alma's change of heart came about, Richard Specht explains this as follows: "I have unwittingly made mischief and need to put things right. In my book about Gustav Mahler, I reported on his Tenth Symphony and said that it had been the master's will for this work to be burnt following his decease .... Only much later did I learn – and Mrs Mahler confirmed this to me – that his wish .... had not been expressed to her, but to his New York friend and physician Dr Josef Fränkel, and indeed that he had spoken to his wife in the last weeks of his life in a quite different tenor, sometimes full of hope as to completion of the work, sometimes of a work which was entirely completed in draft form, with which she was to work at her discretion ... When I found out the true facts, I was the first to adjure Mrs Mahler to bring out the manuscript once more .... She fetched the draft of the five-movement symphony ... and we discovered ... to our great surprise, that two movements of the work .... were so complete in form and recorded in terms of every instrument, that it was possible to simply transfer them from the draft to the form of printed sheet music without changing a single note."  | Liebst Du um Schönheit (Do You Love for Beauty?)

(Lied, "privatissimum" to Alma)

In the summer of 1902, Alma suffered dramatically fluctuating emotions which she could not explain even to herself. "One moment I am overflowing with love for him – and the next moment I feel nothing, nothing!" Her state of mind, oscillating between depressive moods and moral self-accusation, stands in contrast to the cliché of the happy, indeed hopeful wife at the side of a fascinating artist. "And always these tears," she laments in her diary. "I have never cried as much as now, when I have precisely everything a woman can strive for." Mahler too noticed that something was not right with his wife. He reacted in his own way, by composing a song for her. He designated his setting of the Rückert poem Liebst Du um Schönheit as "Privatissimum to you". While Alma was delighted at this gift, the basic problem arising from her discontent with herself was not thereby resolved. "Often I feel how insignificant I am and how little I have compared with his immeasurable wealth!" Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen (I Have Become Lost to the World)

(Love song) Primal Light - Urlicht (Jewish roots in Mahler's music)

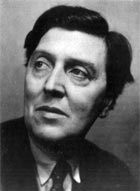

Transcriptions exist of Mahler's music by American jazz composer Uri Caine, "Primal light" – Urlicht, from the Second Symphony, in which he filters out the European elements and places the Jewish elements of Mahler's music at the forefront. ALEXANDER ZEMLINSKY (Composition tutor & Alma's lover)  |  |  |  | | | | | | | Alma Schindler 1900 | | Alexander Zemlinsky | | In the spring of 1900, Alma, then aged 20, met Alexander von Zemlinsky. The 29-year-old composer was considered one of the great hopes of the Viennese music scene. When Alma saw him for the first time at a symphony concert, appalled, she noted the following in her diary: "A caricature – chinless, small, with bulging eyes and a maniacal way of conducting." Just over two weeks later, she met the composer personally at a soirée and still found him dreadfully ugly; "he has almost no chin – and yet he pleased me exceptionally." That evening, Alma and Zemlinsky conversed at length about Richard Wagner, and Wagner's Tristan in particular. When Alma revealed to him that this work was her favourite opera, Zemlinsky was so delighted that he became unrecognizable. He became veritably attractive. "Now we understood one another. I like him very much – very much." An intense relationship soon evolved between the attractive and confident Alma and the reserved Zemlinsky. Under his guidance, the musically-gifted young lady composed a series of Lieder. Then from the autumn of 1900, their relationship became more than one of teacher and pupil. Zemlinsky and Alma Schindler began a love affair which was as passionate as it was problematic. She allowed him to kiss her, caress her, and permitted him every intimacy other than the ultimate, thereby almost robbing him of his reason. The relationship was a roller coaster of emotions. Alma tortured Zemlinsky for two years until, in 1902, she decided against him and in favour of marriage to Gustav Mahler, who was twenty years her senior. Following Alma's marriage to Mahler, initially the contact between the two broke off, but after 1903, once again there began a regular exchange of letters and meetings between the two. Even many years after their love affair, an encounter with Alma Mahler triggered strong feelings in him. When, in 1917, Alma commented negatively on Zemlinsky's opera Eine florentinische Tragödie (A Florentine Tragedy), he reacted with one of his rhetorically most brilliant letters, full of acuity and emotion. Numerous works by Zemlinsky are either dedicated to Alma or reflect the relationship between the beautiful, unattainable woman and the "ugly gnome". (Der Geburtstag der Infantin – The Birthday of the Infanta) Zemlinsky's song Symphony "Lyric Suite " is a reflection on the unfortunate love for Alma. Zemlinsky was inspired to it by Gustav Mahler's "Das Lied von der Erde", but refused letting his work premiered together with Mahler's unfinished 10th Symphony which was Mahler's reaction to Alma's love affair with the architect Walter Gropius. > read more: Part 2 of Alma in the music of other composers | |