| Reserl (Hulda)

chambermaid In 1918, Kokoschka, twice wounded in the war, and seriously shell-shocked, was convalescing in Dresden. He lodged in the house of Dr Posse, director of the Dresden Art Gallery, who kept a serving-maid, "a pretty young Saxon girl by the name of Hulda. She had imagination," Kokoschka remembered, "which is why she attracted my attention."  |  | | | | | | Oskar Kokoschka:

"Girl with Doll" (Reserl) (1921/22) | Oskar and Reserl, as the artist rechristened Hulda, liked to play games: "When she served in my rooms she played the part of a lady's maid, for which I provided her with a cap and a batiste apron, together with black silk stockings bought from a reserve soldier who had knocked around Paris for a few years and now kept a black-market store." "Above all Reserl helped with the fantasy game I played with my doll", Kokoschka reported - a doll that was intended to be an exact, life-size replica of his former lover Alma Mahler, who, by that time, had already moved on to poet Franz Werfel. "I wanted to have done with the Alma Mahler business once and for all," Kokoschka admitted, "and never again to fall victim to Pandora's fatal box, which had already brought me so much suffering..." Kokoschka commissioned the doll in summer 1918 from the Munich avant-garde puppet-maker Hermine Moos. The artist's instructions, conveyed in a mass of letters and drawings between August 1918 and February 1919, were painstakingly detailed: "Yesterday I sent a life-size drawing of my beloved and I ask you to copy this most carefully and to transform it into reality. Pay special attention to the dimensions of the head and neck, to the ribcage, the rump and the limbs. And take to heart the contours of body, e.g., the line of the neck to the back, the curve of the belly. Please permit my sense of touch to take pleasure in those places where layers of fat or muscle suddenly give way to a sinewy covering of skin. For the first layer (inside) please use fine, curly horsehair; you must buy an old sofa or something similar; have the horsehair disinfected. Then, over that, a layer of pouches stuffed with down, cottonwool for the seat and breasts. The point of all this for me is an experience which I must be able to embrace!" In December Kokoschka eagerly demanded of Hermine Moos: "Can the mouth be opened? Are there teeth and a tongue inside? I hope so!" "I would die of jealousy," Kokoschka told Moos in January 1919, "if some man were allowed to touch the artificial woman in her nakedness with his hands or glimpse her with his eyes! When shall I be able to hold all this in my hands?"  |  | | | | | | Oskar Kokoschka: Reserl | So fixated was Kokoschka on the impending delivery of "my beloved, for whom I am pining away," that not even the charms of pretty Reserl, "whom no man had ever seen naked," could distract him. Reserl herself was very much in love with her master, whom she referred to as »captain«, and to whom she showed every conceivable devotion. She even carved his initials into her own breast with a knife. Kokoschka remembered that Reserl one day crept into his bed, whispering into his ear: "I am at your service body and soul - dispose of me, Sir." One day Dr Posse's father died, and Kokoschka was asked to draw a portrait from the corpse before the undertaker arrived. It was not a job he relished, and it depressed him. Reserl sought to give him comfort: "Alone, I worked on my drawing far into the night. Afterwards, wanting a bath, I descended the dark stairs into the cellar, where stood a tall water-butt for use of the whole household. Moonlight shone through the cellar window, and there, to my surprise, like Undine in the story, Reserl emerged from the water. With a provocative casualness she said that she simply wished to take my mind off thoughts of death... I liked the way she blushed so readily; but by now I was preoccupied with anxious thoughts about the arrival of the doll, for which I had bought Parisian clothes and underwear."  | | | | The notorious Alma doll, a life-size copy of Alma | The doll arrived in a large packing case full of shavings in spring 1919. Inevitably it was a disappointment: "I was honestly shocked by your doll," Kokoschka wrote to Hermine Moos, "which, although I was long prepared for a certain distance from reality, contradicts what I demanded of it and hoped of you in too many ways!" Despite his request for a skin that feels like natural skin, Moos' creation had a skin of feathers: "The outer shell is a polar-bear pelt, suitable for a shaggy imitation bedside rug rather than the soft and pliable skin of a woman. The result is that I cannot even dress the doll, which you knew was my intention, let alone array her in delicate and precious robes. Even attempting to pull on one stocking would be like asking a French dancing-master to waltz with a polar bear!" Nevertheless Kokoschka had eyes only for Alma's Double, to whom he now transferred the extreme possessiveness on which his relationship with the doll's life-model had foundered: "Reserl and I called her simply the "Silent Woman". Reserl was commissioned to spread rumours about the charms and mysterious origins of the Silent Woman: for example, that I had hired a horse and carriage to take her out on sunny days, and rented a box at the Opera in order to show her off."  |  | | | | | | Oskar Kokoschka:

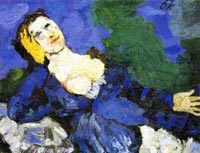

"Woman in Blue" (1919) | "In a state of feverish anticipation, like Orpheus calling Eurydice back from the Underworld, I freed the effigy of Alma Mahler from its packing. As I lifted it into the light of day, the image of her I had preserved in my memory stirred into life. The light I saw at that moment was without precedent. The cloth-and-sawdust effigy, in which I vainly sought to trace the features of Alma Mahler, was transfigured in a sudden flash of inspiration into a painting - "The Woman in Blue". The larva, after its long winter in the cocoon, had emerged as a butterfly." After having expended so much energy and expense on the doll's creation, Kokoschka, a few months later, decided to dispose of the fetish. He decided to have a big Party, with champagne for all his friends, and there put an end to his inanimate companion:  |  | | | | | The Puppet | | "I engaged a chamber orchestra from the Opera. The musicians, in formal dress, played in the garden, seated in a Baroque fountain whose waters cooled the warm evening air. A Venetian courtesan, famed for her beauty and wearing a very low-necked dress, insisted on seeing the Silent Woman face to face, supposing her to be a rival. She must have felt like a cat trying to catch a butterfly through a window-pane; she simply could not understand. Reserl paraded the doll as if at a fashion show; the courtesan asked whether I slept with the doll, and whether it looked like anyone I had been in love with... In the course of the Party the doll lost its head and was doused in red wine. We were all drunk." The following morning Kokoschka was woken by the police, who were investigating a report of a possible murder. "In our dressing gowns we went down to the garden, where the doll lay, headless and apparently drenched in blood." Matters were explained, Dr Posse smoothed things over, and the corpse was removed.  |  | | | | | | Oskar Kokoschka:

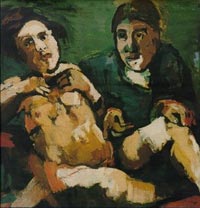

"Self-portrait with Doll" (1920/21) | "The dustcart came in the grey light of dawn, and carried away the dream of Eurydice's return," Kokoschka remembered. "The doll was an image of a spent love that no Pygmalion could bring to life." Kokoschka drew and painted the doll in many poses, usually of sexual availability. In his picture "Self-portrait with Doll", which he painted from memory in 1920/21, she lolls beside him on a sofa, naked. Kokoschka is fully clothed. It is significant that he is pointing to the doll's sexual parts with a look of resignation and indifference. Reserl's vanished from Dresden in the 1920s, and today no-one knows what has become of her... | |