| La Grande Veuve (1945 - 1964)  |  |  | | | | | | Alma with a score of Gustav Mahler's,

at her house in Beverly Hills | | Alma with a portrait of Gustav Mahler | In the last 19 years of her life, Thomas Mann described Alma Mahler-Werfel as "la Grande Veuve", the "Great Widow" of Gustav Mahler and Franz Werfel. Claire Goll's assessment of the widow was more malicious. In Goll's view, after Werfel's death Alma turned her eye to Bruno Walter. She compared Alma Mahler, whose predilection for champagne and Bénédictine did not reflect positively in her figure, with a "bulging Germania", and wrote of her: "In order to freshen up her fading charms, she wore gigantic hats with ostrich feathers; nobody knew whether she wished to appear as a funeral horse pulling a hearse, or as a new d'Artagnan. On top of that, she was powdered, made up, perfumed and inebriated. This bloated Valkyrie drank like a fish." | |

|  |  |

| | | | Alma Mahler-Werfel

(Caricature by Dolbin) | | Alma on her arrival at the airport

in Tulln near Vienna in September 1947 | Alma Mahler-Werfel only revisited her old home city of Vienna briefly on one occasion in 1947. Her mother had died in the autumn of 1938; her stepfather Carl Moll, her half-sister Maria and Richard Eberstaller, who had both been longstanding members of the Nazi Party, had committed suicide in April 1945. Her visit revolved mainly around settling financial matters. She embroiled herself in court proceedings with the Austrian state over Edward Munch's painting "Summer Night on the Beach", which Walter Gropius had given her once on the occasion of the birth of their joint daughter, and which, following Alma's emigration to the USA in April 1940, Carl Moll had sold to what is now the Austrian Belvedere Museum. Alma lost the case, because she could not credibly substantiate that her stepfather had done this without her consent. The proceeds of sale of the picture had moreover been used n order to carry out necessary repairs to her house on the Semmering. Moll had not been personally enriched. Until the 1960s, she strived to recover the painting, and refused to tread on Austrian soil again. In the court proceedings there was also mention of the fact that, at the end of the 1930s, Alma had attempted, via her brother-in-law, to sell Anton Bruckner's handwritten manuscript of the first three movements of his 3rd Symphony to the Nazis. | |

|  |  |

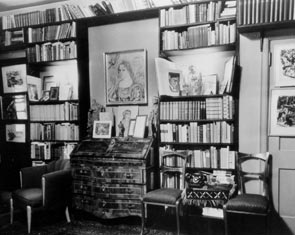

| | | | Alma Mahler-Werfel with portrait of her

deceased husband, Franz Werfel | | Alma at Werfel's desk in her house in Los Angeles | For her 70th birthday, Alma Mahler-Werfel received an unusual present which also documents the extent to which she was indebted to the cultural scene. Months before her birthday, a couple she knew had written to her friends and acquaintances and asked them each to write on a sheet of paper. Among the 77 well-wishers who transmitted their congratulations in this way in a birthday book, were her former husband Walter Gropius, Oskar Kokoschka, Heinrich and Thomas Mann, Carl Zuckmayer, Franz Theodor Csokor, Lion Feuchtwanger, Fritz von Unruh, Willy Haas, Benjamin Britten, her former son-in-law Ernst Krenek, Darius Milhaud, Igor Stravinsky, Ernst Toch, conductors Erich Kleiber, Eugene Ormandy, Fritz Stiedry and Leopold Stokowski, as well as former Austrian Chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg. Arnold Schönberg, who had not been invited to contribute to the book due to a previous quarrel with Alma, dedicated a birthday canon to her with the text: "Centre of gravitation of your own solar system, orbited by radiant satellites, this is how your life appears to the admirer." The autobiography "And the Bridge is Love"

In 1951 Alma moved to New York, where she had bought four small residential apartments in a house on the Upper East Side. She herself lived on the third floor, and used one apartment as a living area and another as sleeping quarters. The two apartments on the floor above were used by August Hess, Werfel's former valet, and by her guests. For some time already she had been working on her autobiography, which was based on her diaries. She was initially supported by Paul Frischauer as ghost-writer, but they had fallen out with one another back in 1947 when he criticized her numerous anti-Semitic slurs. In the 1950s she worked with E. B. Ashton. He too perceived the necessity to censor her diaries due to her anti-Semitic utterances and numerous attacks on people who were still living. In 1958, "And the Bridge is Love" appeared in English.  |  |  | | | | | | Alma's house in NY,

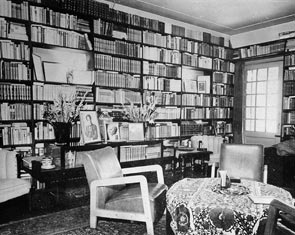

120 East 73rd Street | | Alma's library in her New York apartment,

with portrait of Gustav Mahler | The reactions to this English edition were muted. In particular, Walter Gropius reacted angrily, hurt by the representation of their earlier love affair. The reactions of other friends and acquaintances, such as Paul Zsolnay, made it clear to Alma that a German-language edition, which had already been contemplated, should not be published without significant changes to the text. Willy Haas was given the task of preparing an edition for the German-speaking market, and was to smooth over the original text still further. Alma's previous ghost-writers had already suggested to her that she delete her racist political views. It was only the reactions to the English edition which changed her mind: "Please remove all traces of the whole Jewish question," she wrote to Willy Haas.  |  |  | | | | | | Alma's music room in her New York apartment, with a painting by her father, Emil Jakob Schindler | | Alma with conductor Eugene Ormandy | Her German-language biography, "Mein Leben" (My Life), in no manner found the positive reception which Alma had expected. The book was considered "salacious", ambiguous, and contradictory, and provoked caricature due to its egocentric presentation. Long-term friends such as Carl Zuckmayer and Thomas Mann had already distanced themselves from her following publication of the English version.  |  |  | | | | | | Alma Mahler, New York 1962, two years before her death | | Alma's library in her New York apartment, with the famous portrait by Oskar Kokoschka showing

her as Lucretia Borgia | Alma's death

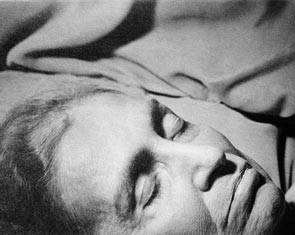

Alma Mahler-Werfel died in her New York apartment on 11 December 1964 at the age of 85. The first funeral ceremony took place two days later, with Soma Morgenstern giving the eulogy. However, Alma was not buried until 8 February 1965, beside the grave of her daughter Manon in Vienna's Grinzing Cemetery. The obituaries which appeared after her death referred, under the influence of her autobiography, mostly to her marriages and love affairs. The combination of attraction, admiration and antipathy which she triggered in many is also expressed in a poem written and published spontaneously by songwriter and satirist Tom Lehrer after her death.  |  |  |

| | | | Alma on her deathbed (photographed by Trude Fleischmann, December 1964) | Friedrich Torberg's obituary for Alma Mahler-Werfel, published in 1964, explains why so many creative artists were fascinated by her: "Whenever she was convinced by a person's talent, she left such person - often with an energy bordering on brutality - no further path open other than that of fulfilment. They were then under a duty in relation to themselves and to her and the world, and she experienced it as a personal affront if a gift which she had recognized or indeed promoted was not then generally acknowledged. Incidentally, this happened to only a few, and to them she remained affectingly loyal. Success bewitched her, but lack of success did not divert her. Her enthusiasm, her commitment, her ability to sacrifice herself knew no bounds, and must have been both a fascination and an incitement purely for the reason that there was no hint of uncritical idolization about her, because her powers of judgment refused to be clouded by anything. This was undoubtedly also the reason why so many creative men stuck with her. This was the place where their own productivity progressed and bore fruit [...] . She had a way of arranging and directing which, with a geometric inevitability, made her the figure at the centre, and all were content with this, since this central figure stood firm and, rather than herself, placed the others centre-stage." < back: Emigration (1938 - 1945)

< The most beautiful girl in Vienna (1879 - 1901) | |